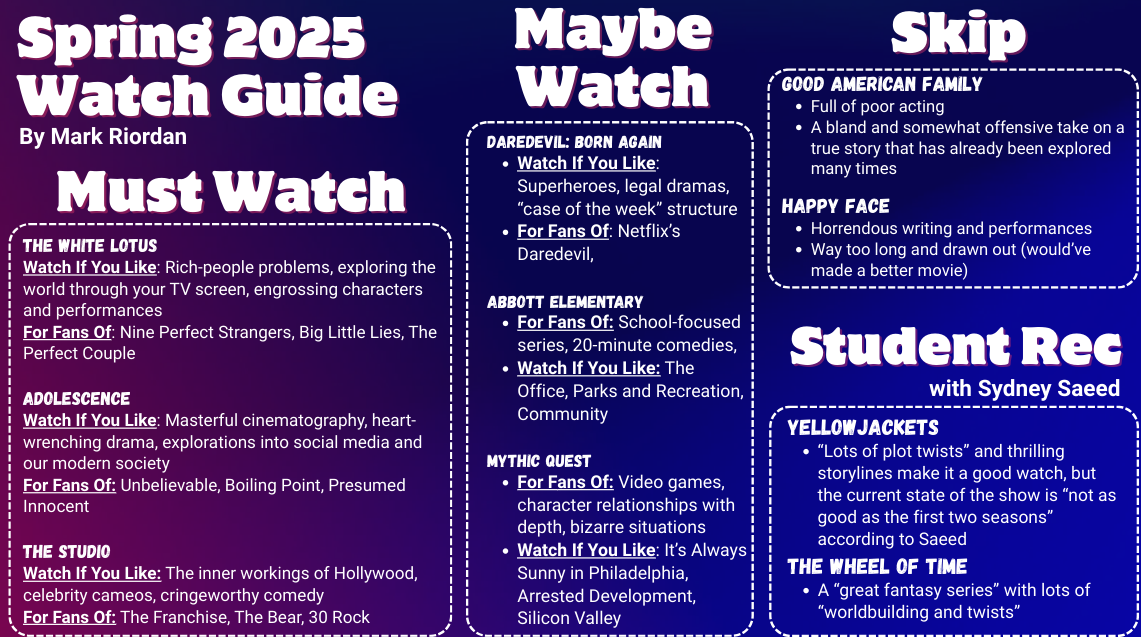

Woman of The Hour is a movie just as bone-chilling as it is impactful. This is, surprisingly, not because its plot follows a prolific and brutal serial killer. Instead, Woman of the Hour’s true horror comes from the skill with which it reveals, in haunting clarity, the realities of womanhood.

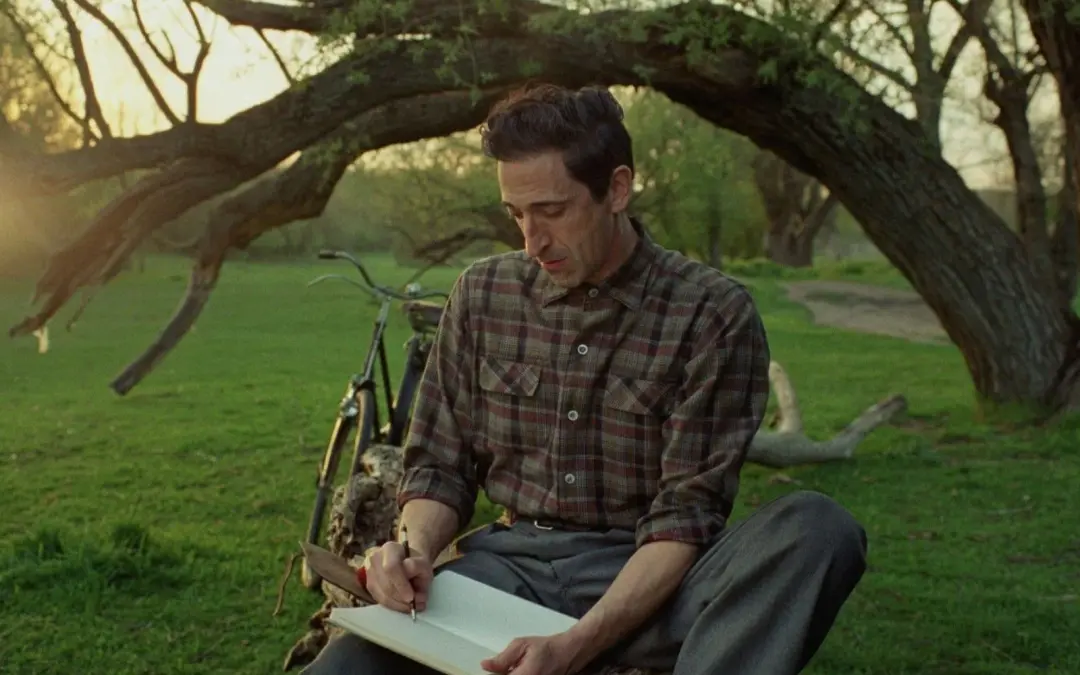

The movie features actor Daniel Zovatto, who portrays the real-life serial killer and rapist Rodney Alcala. Alcala has been tied to eight murders, but his true number of victims is unknown and has been estimated to number in the hundreds.

In a market saturated by depictions of serial killers ranging from reverential to shocking, Woman of the Hour stands out. This is because the movie is fundamentally not about Alcala.

Instead, it is about those he killed and abused, who are portrayed not as victims, but as women. There’s Sarah, pregnant and devastated by her recent breakup. Amy, a sardonic teen runaway. Charlie, an outgoing flight attendant. And finally, the film’s main character, Cheryl Bradshaw, a clever struggling actress in Los Angeles portrayed by actress Anna Kendrick.

The film follows the ins and outs of Bradshaw’s daily life, segmented by flashes of the violent encounters other women have with Alcala. These flashes are sickening in their violence and in their reality: in the knowledge that all the onscreen atrocities of the movie happened to real, live women. But, intriguingly, it is not just these moments of action that are sickening. The entire movie is permeated by a miasma of gut-clenching, heart-spiking fear.

This fear creeps in when Bradshaw’s male friend hits on her at the beginning of the movie, and her face drops. When she finally accepts his advances because he won’t let it go. When she’s alone in an audition room full of male producers making crude jokes. When Alcala walks towards Charlie and her eyes widen in useless realization. When a woman recognizes Alcala as the man who murdered her friend but realizes that neither her boyfriend nor the police will believe her. It is these subtle moments when female characters realize how truly powerless they are that create the film’s eerie and captivating atmosphere of anxiety.

The dark and dire themes of Woman of the Hour are complemented by cinematic mastery. At the secluded locations Alcala brings many of his victims, stunning wide shots of grass swaying and blue mountains sweeping across the horizon enhance the tragedy of the film. The mountains and greenery stand silent witness to the violence Alcala inflicts, creating a sense of hopelessness. This hopelessness reinforces the film’s depiction of womanhood as perilous, which is further enhanced by exceptional acting. Kendrick flawlessly brings to life the quiet terror of Bradshaw, and Zovatto depicts Alcala with unnerving charisma that gives way to cold fury at the drop of a hat.

The writing, filmmaking, and acting of Woman of the Hour synchronize in a beautiful crescendo ending in a devastating condemnation: women live in a man’s world. And so they live in constant fear and quiet strength, clutching their wits about them and choking down tears.

*Opinions expressed in this article represent the views of the editorial staff and not necessarily those of the school population or administration.